|

Floor Plan |  |

The Dennis Wheatley 'Museum' - Dennis Wheatley's Writing Technique

Making people want to turn the page

This is what DW said in his various books and interviews about how he wrote is books, once planned:

The beginning, the middle and the end:

[The] book must have a definite structure, and two things he should aim for are a good beginning and a good end. It is of the first importance that in the opening chapters, or preferably chapter, he should clearly present a gripping situation. His principal characters must be confronted with some menace to their lives or happiness, be called on to avert some terrible disaster, or to undertake some exciting quest. Only so can he hope firmly to engage the attention of his readers. The end is as much, or perhaps even more importance. And that, of course, is where so many whodunits fall down. After the cat has been let out of the bag the reader is still expected to wade through another ten thousand words of explanation. If the denoument can be kept to the very last page, and it is a good one, the reader's next thought after finishing the book will be, 'I must get hold of another book by this author.' The middle of every book consists of a series of episodes, and the more it resembles a game of snakes and ladders the more likely it is to hold the reader's interest.

[DW's Cantor lecture]

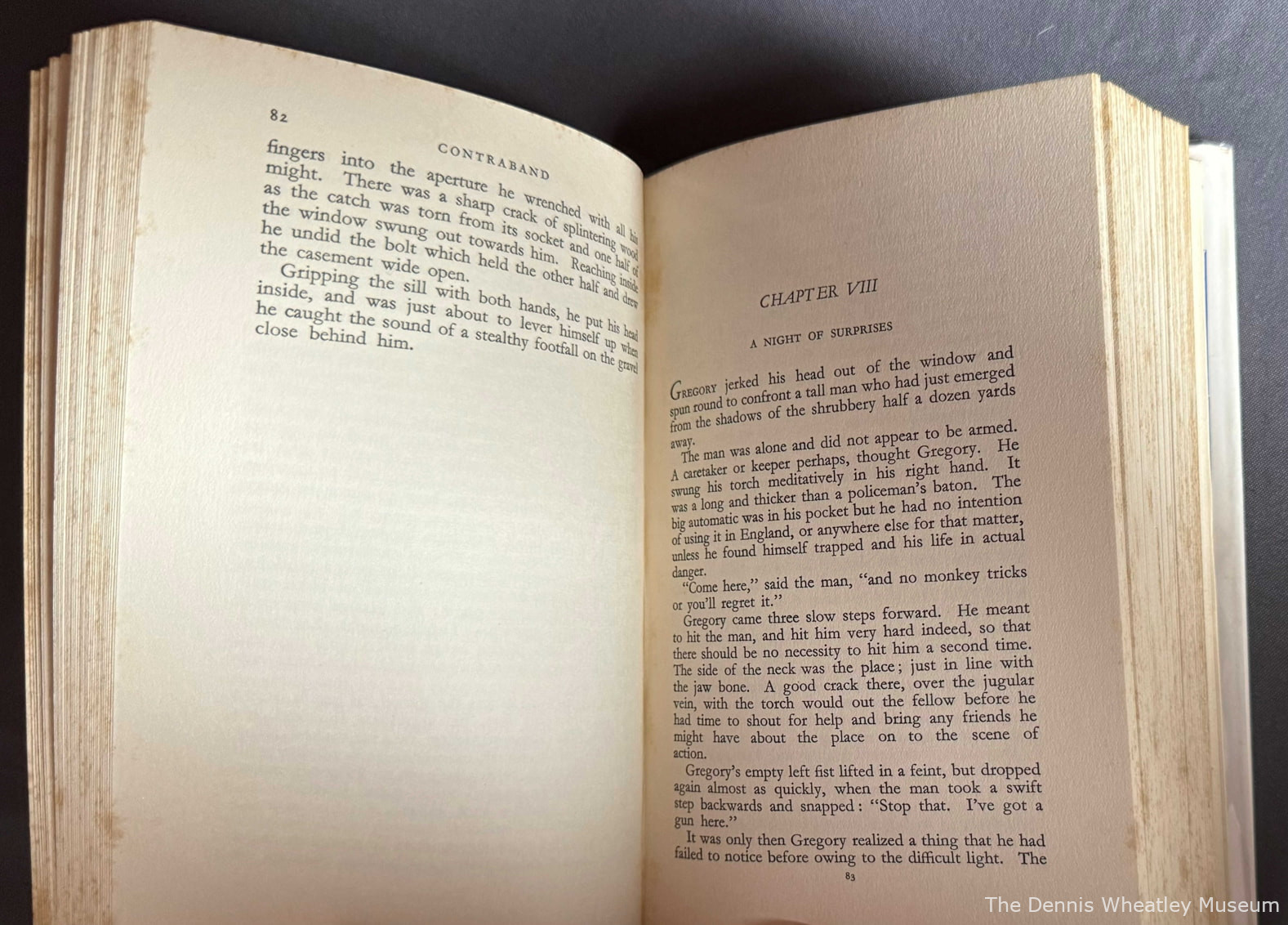

Prolonging the action and ending the chapters in 'mid-air':

[In] the scenes of crisis, must be very long. You notice in most thrillers, where there is a fight, it's all over in half a page. One needs to prolong that, without using the same term twice. On the other hand, the background, you must have it, but you want to put it in so there is not took much background holding up the story. And that's the blend. And, of course, leaving people in the air. I do what was very unusual in those days. In fact I don't think anyone had ever done it that way, in that I broke off at chapter ends in the middle of a situation, so that people had to turn the page to the next chapter to see what happens, and of course that was a very good technique.

[DW's interview with Robert Robinson]

A superb beginning and a superb end:

Of course as I say, there are these techniques, like, for example, one always must have a smashing end to one's last chapter. All these detective stories - and I never write detective stories, I don't like them - but this business of explaining why the butler wasn't there at the appointed time or whatever, is dreary beyond belief, and that sort of thing happens in other types of fiction, and I don't believe in that at all. I build the thing up, so that when I get to the last chapter, I always quote, like going round Tattenham Corner, and I can write 5,000 words... go straight home, and people put that book down and they say 'God, Who wrote this book?', 'Oh, Dennis Wheatley! I must get another' and otherwise, I don't know, it's really, it boils down I suppose to the capacity to tell a good story, that's really the answer.

[DW's interview with Robert Robinson]

Blending fact with fiction:

My books were, on average, about 160,000 words, which is over twice the length of the ordinary thriller. But in the fact that my books were not ordinary thrillers lies the secret of their success. Actually to create each book I wrote a combined two. One of these would consist of a history of Ceylon or Mexico, or of a period in the Napoleonic or Hitler wars. Into these factual accounts I wove a spy story, desperate situations and boy jumping into bed with girl.

This blend proved amazingly successful as many people who normally never read thrillers would read a 'Wheatley' for the pleasure of recalling the country described, if they had visited it, or to learn about it or about some interesting historical events.

[Drink and Ink p 251]

Regarding grammar:

Robert Robinson: As you're writing it, do you not bother how you're putting it down, so long as the story is good enough?

DW: I write to make it plain to the reader what is going on, and I couldn't care less if it's grammatical or its not grammatical as long as it's perfectly clear to the reader, you see, and on that, I simply write. And if the highbrow critics don't like the way it's put, well they can go and write better books and make more money. [LAUGHS]

[DW's interview with Robert Robinson]

| References: | DW's Cantor Lecture for the Royal Society of Arts, 1953. |

| DW's interview with Robert Robinson for 'The Book Programme', 1977 |